November 1, 2016

By Mary Schmich, Chicago Tribune

CT-GregDell-BroadwayUMC.jpg

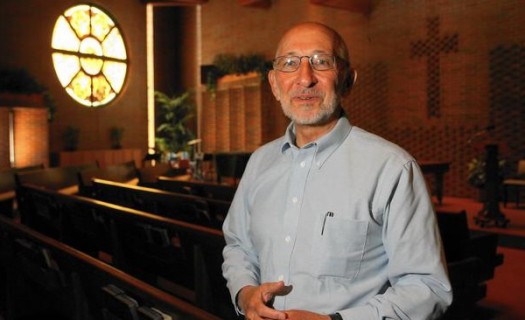

The Rev. Greg Dell in the sanctuary of Broadway United Methodist Church in 2007. Dell was suspended from his duties at the church for performing a gay union in 1998.

On days when it seems that the world is tumbling backward, it helps to remember how far we've come.

The death of the Rev. Greg Dell on Sunday, at the age of 70, is one reminder.

Dell was once the pastor of Broadway United Methodist Church in Chicago's Lakeview East neighborhood. If you'd passed him on the street — a middle-age man, compact, quiet dresser — there was nothing about him to make you think, "There goes a revolutionary."

But he was a revolutionary, willing to lose his job in the name of justice.

I met Dell in December 1998, shortly before he was to go on trial in a Methodist church court. I can still see the cool, dark sanctuary, the sunlight filtering through the stained glass windows, as he pulled open the wooden door and said, "The scene of the crime."

The crime was officiating at a "service of holy union" ceremony for two gay men.

It may be hard in this era of legal gay marriage for young people to fathom how radical and controversial Dell was.

"He was one of the most powerful allies our community has had in the 32 years I've been covering the community," says Tracy Baim, publisher of the Windy City Times. "He was inspirational in doing what was right despite the forces against him."

By the mid 1990s, when Dell and his wife, Jade, came to Broadway United, the rhetoric of gay rights had penetrated American culture, but gay marriage wasn't high on the agenda, and although some denominations had welcomed gay people, the Methodist church was resistant.

But Dell believed he was there to serve his congregation, and his congregation included many gay people.

"Our church attracted a lot of what I describe as 'wounded birds,'" said Jim Bennett, a longtime congregant who met his husband at the church, "people who had been kicked out of their churches and their families. Every denomination was represented. He felt a responsibility to help them restore their faith."

Restoring faith meant helping people who loved each other commit to each other as a couple in the embrace of the church community.

Dell grew up in the white, blue-collar suburb of Midlothian, the son of a police officer, which may not seem like fertile ground for activism, but the 1960s put him on alert. Racism. Sexism. The world needed changing.

He was at Duke Divinity School when Martin Luther King Jr. was shot to death, an event he called his "faith conversion experience."

"I realized then there was something more powerful than the power of death," he said the day we talked. "If you played it safe, stayed out of the issues, you could never experience the full life. But if you took on the full life, you'd experience loss and hurt."

He chose the full life.

Dell had officiated at unions for gay couples for many years, quietly, before publicity caught up with him. When it did, the news was national. So was the abuse.

After learning about Dell's pending church trial, Fred Phelps, the head of a Kansas-based church opposed to homosexuality, led a small band of picketers to Broadway United. They clogged the sidewalk pumping signs: "Fags Die God Laughs," "Methodist Fag Church," "False Prophet Dell."

A few months later, in March 1999, a jury of Methodist ministers voted to suspend Dell indefinitely from his job for violating church law.

"It was horrible," says Bennett. "I'm fairly confident Greg always believed that they wouldn't find him guilty because he truly believed that his moral obligation was to serve the people of his church."

Eventually, the suspension was limited to a year, and Dell returned to his church to preach for a while longer. In 2006, he was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, which crippled, among other things, his ability to speak.

"It was like he'd been kidnapped," Bennett said. "He is not a person who was supposed to be silent."

But as Dell struggled with Parkinson's for the past decade, he didn't abandon his causes. In the Chicago nursing home where he lived for a while, Bennett said, he was trying to organize the workers to demand better pay.

At the time of his death, Dell and his wife lived in Raleigh, N.C. The weather was easier.

"He's Chicago through and through," Bennett said, "but it provided a good place for them and even a good place for them to protest."

A few months ago, Bennett said, Dell, in a wheelchair, attended a protest on behalf of transgender rights.

When he died Sunday, Greg Dell left a world that was better than the one he was born into. He helped make it that way.

A full life.